Marine Biodiversity

Coastal zone: Marine Ecosystem

Marine ecosystems are the largest of Earth's aquatic ecosystems and are distinguished by waters that have a high salt content. These systems contrast with freshwater ecosystems, which have a lower salt content. Marine waters cover more than 70% of the surface of the Earth and account for more than 97% of Earth's water supply and 90% of habitable space on Earth. Marine ecosystems include nearshore systems, such as the salt marshes, mudflats, seagrass meadows, mangroves, rocky intertidal systems and coral reefs. They also extend outwards from the coast to include offshore systems, such as the surface ocean, pelagic ocean waters, the deep sea, oceanic hydrothermal vents, and the sea floor. Marine ecosystems are characterized by the biological community of organisms that they are associated with and their physical environment.

Coastal zone: Estuarine Ecosystem

Estuarine ecosystem

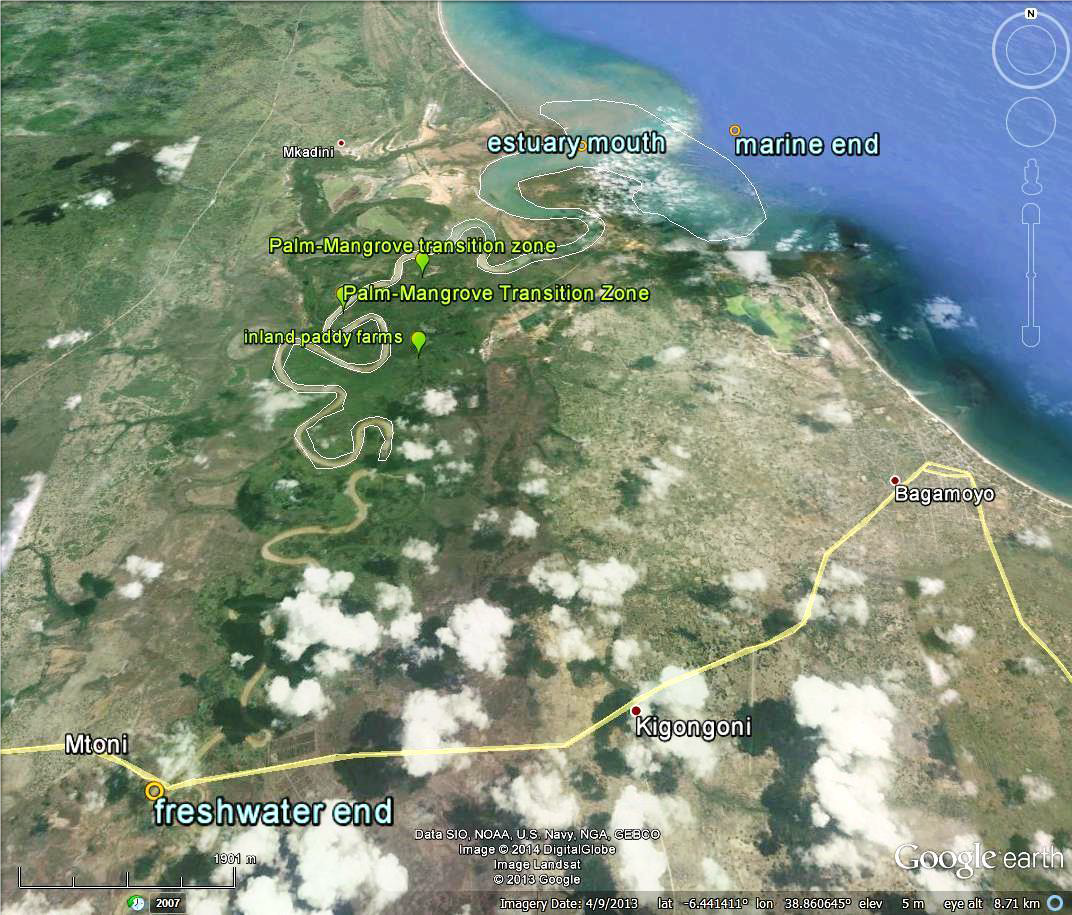

An estuary is defined as a partly enclosed body of brackish water with at least one freshwater river flowing into it and having a free connection to the sea (Pritchard 1967). The major estuaries in Tanzania occur where the rivers Pangani, Wami, Ruvu and Rufiji flow into the Indian Ocean. Estuaries have a unique environment with a constantly varying mix of freshwater and seawater. This mix varies seasonally from a pulse of freshwater flowing far out to sea during the rainy season, to very saline conditions in the estuary during the dry season when the freshwater flow in the river has decreased. The mix of freshwater and saline seawater also varies diurnally with tides; at high tide, the seawater opposes the freshwater and moves into the river as a wedge of denser water flowing in underneath the freshwater that is flowing seaward in the opposite direction.

This ever-changing environment of fresh and saline water along with the nutrients brought by both water pools provides one of the world’s most productive ecosystems - the estuarine and coastal ecosystems. In the tropics, seagrass beds cover the estuary and coastal offshore muddy/sandy bottom, where marine fish come to breed, the seagrass providing both shelter for juvenile fish from larger marine predators of the open sea, as well as food in the form of submerged aquatic vegetation and marine invertebrates (Bwathondi & Mwamsojo 1993). Several species of mangroves frequently are found growing on the river banks and coasts of tropical and subtropical estuarine environments. Their roots protect the coast from erosion and from tropical storms, and also slow down flow thereby facilitating sedimentation and nutrient deposition (Semesi 1991).

Coastal zone: Mangrove Ecosystem

Mangrove ecosystem

Mangroves are the only group of trees able to tolerate salinity, and hence the mangrove to palm (Phoenix reclinata) transition zone indicates the extent of average seawater ingress into the River. Mangroves and seagrass beds are critical nursery areas for marine fish, and coastal fisheries depend on these habitats remaining in a healthy condition. Semesi et al. (2000) described in detail the natural resources in the mangrove forests and the seagrasses and their uses by the local communities. The livelihoods of local human populations often are largely dependent on these resources such as fish and mangrove poles that have been exported for centuries throughout Tanzania and beyond (Martin 1978).

Mangrove species are known to vary in their salinity and flood tolerance (Semesi 1991). This leads to species with the highest flood and salinity tolerance (Sonneratia alba and Rhizophora mucronata) to occur at the edges of the bank that are flooded at high tide followed by Avicennia marina, with intermediate tolerance while mangroves with less tolerant of flooding such as Ceriops turgle, Xylocarpus and Hereteria occupy higher ground inland, that also have sandier soil while the shores have more loam and organic content.

This horizontal zonation of mangroves can be monitored periodically along with salinity measurements to constitute a long-term seawater intrusion monitoring program. Nonetheless seawater intrudes further upstream in the dry season coinciding with the lowest freshwater inflow and spring tide combination extends the boundary of salinity inland.

Coastal zone: Coral Reef Ecosystem

Coral reef ecosystem

Coral reefs are one of the most biologically diverse ecosystems on earth, rivaled only by tropical rain forests. They are made up not only of hard and soft corals, but also sponges, crustaceans, mollusks, fish, sea turtles, sharks, dolphins and much more. Competition for resources such as food, space and sunlight are some of the primary factors in determining the abundances and diversity of organisms on a reef. Each component of a coral reef is dependent upon and interconnected with countless other plants, animals and organisms. This means that fluctuations in the abundance of one species can drastically alter both the diversity and abundances of others. While natural causes such as hurricanes and other large storm events can be the stimulus for such alterations, it is more commonly anthropological forces that affect these types of shifts in the ecosystem.

The health, abundance and diversity of the organisms that make up a coral reef is directly linked to the surrounding terrestrial and marine environments. Mangrove forests and seagrass beds are two of the most important facets of the greater coral reef ecosystem. Mangroves are salt-tolerant trees that grow along tropical and sub-tropical coasts. Their complex root systems help stabilize the shore line, while filtering pollutants and producing nutrients. Their submerged roots and detritus provide nursery, breeding, and feeding grounds for invertebrates, fish, birds, and other marine life. Many of the animals raised in mangroves migrate to coral reefs for food, spawning and habitat.

Seagrasses are flowering plants that often form meadows between mangrove habitats and coral reefs. They form the foundation of many food webs, providing nutrients for everything from sea urchins and snails to sea turtles and manatees. Seagrass also provides protection and shelter for commercially valuable species such as stone crabs, snappers and lobsters. Additionally, they filter the water column, prevent seabed erosion, and release oxygen essential for most marine life.

The ecosystem services of mangroves and seagrass are vital to the long term health of coral reefs. There is another very important element of the reef ecosystem that is often over looked: the land. Pollutants, nutrients and litter enter near shore waters through rivers, streams, underground seepage, waste water and storm water runnoff. Even areas hundreds of miles from the coast can affect the clarity and quality of water flowing to the reef. It does not matter how far removed a pollutant may seem, it all flows down stream and it can all impact our marine environment and our reefs.

These coastal ecosystems interact with each other and together sustain a tremendous diversity of marine life, which is an important source of sustenance for coastal communities. For instance, a wide range of important and valued species are found, including an estimated 150 species of coral in 13 families, 8,000 species of invertebrates, 1,000 species of fish, 5 species of marine turtles, and many seabirds.

Environmental degradation, as well as a decline in natural resources and biodiversity are beginning to become more obvious. This is evidenced by declining yields of fish, deteriorating conditions of coral reefs, and continuing reduction in the area of mangroves and coastal forests. This degradation is attributed to unsustainable use of coastal resources as well as pressures from the growing coastal population and climate change impact.

Various management responses have been (or are being) undertaken at different governance levels in the attempt to manage coastal and marine resources sustainably. These responses include traditional management systems, collaborative management arrangements, and enforcement of policies and laws through regulatory mechanisms. Despite all these efforts, problems of biodiversity loss, pollution, and habitat destruction and degradation continue to increase indicating clearly deficiencies in the existing management frameworks.